For more information about FIDL's overall purpose, goals, and requirements, see the concepts overview.

Core Concepts

Message

A FIDL message is a collection of data.

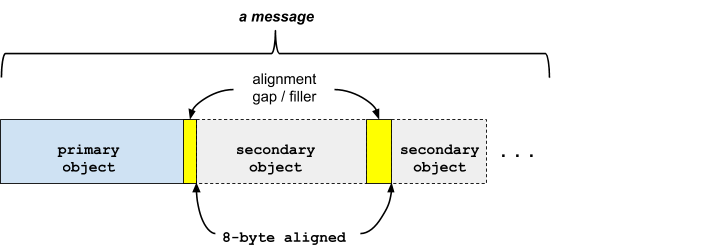

The message is a contiguous structure consisting of a single in-line primary object followed by zero or more out-of-line secondary objects.

Objects are stored in traversal order, and are subject to padding.

Primary and Secondary Objects

The first object is called the primary object. It is a structure of fixed size whose type and size are known from the context. When reading a message, it is required to know the expected type to be read, i.e. the format is not self-describing. The context in which a read occurs should make this unambiguous. As an example, in the case of reading messages as part of IPC (see transactional message header), the context is fully specified by the data contained in the header (in particular, the ordinal allows the recipient to know what is the intended type). In the case of reading data at rest, there is no equivalent descriptor, but it is assumed that both encoder and decoder have knowledge about what type is being encoded or decoded (for example, this information is compiled into the respective libraries used by the encoder and decoder).

The primary object may refer to secondary objects (such as in the case of strings, vectors, unions, and so on) if additional variable-sized or optional data is required.

Secondary objects are stored out-of-line in traversal order.

Both primary and secondary objects are 8-byte aligned, and are stored without gaps (other than those required for alignment).

Together, a primary object and its secondary objects are called a message.

Messages for transactions

A transactional FIDL message (transactional message) is used to send data from one application to another.

The transactional messages section, describes how a transactional message is composed of a header message optionally followed by a body message.

Traversal Order

The traversal order of a message is determined by a recursive depth-first walk of all of the objects it contains, as obtained by following the chain of references.

Given the following structure:

type Cart = struct {

items vector<Item>;

};

type Item = struct {

product Product;

quantity uint32;

};

type Product = struct {

sku string;

name string;

description string:optional;

price uint32;

};

The depth-first traversal order for a Cart message is defined by the following

pseudo-code:

visit Cart:

for each Item in Cart.items vector data:

visit Item.product:

visit Product.sku

visit Product.name

visit Product.description

visit Product.price

visit Item.quantity

Dual Forms: Encoded vs Decoded

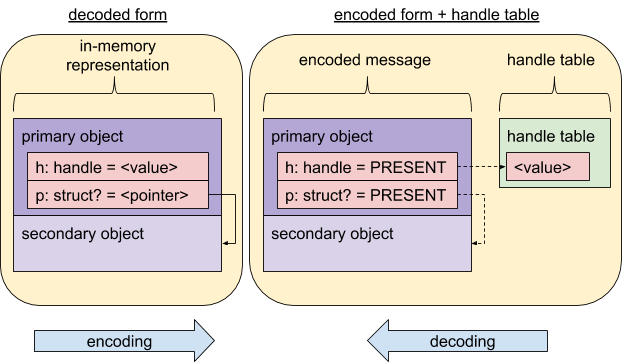

The same message content can be expressed in one of two forms: encoded and decoded. These have the same size and overall layout, but differ in terms of their representation of pointers (memory addresses) or handles (capabilities).

FIDL is designed such that encoding and decoding of messages can occur in place in memory.

Message encoding is canonical — there is exactly one encoding for a given message.

Encoded Messages

An encoded message has been prepared for transfer to another process: it does not contain pointers (memory addresses) or handles (capabilities).

During encoding...

- All pointers to sub-objects within the message are replaced with flags that indicate whether their referent is present or not-present,

- All handles within the message are extracted to an associated handle vector and replaced with flags that indicate whether their referent is present or not-present.

The resulting encoded message and handle vector can then be sent to another process using zx_channel_write() or a similar IPC mechanism. There are additional constraints on this kind of IPC. See transactional messages.

Decoded Messages

A decoded message has been prepared for use within a process's address space: it may contain pointers (memory addresses) or handles (capabilities).

During decoding:

- All pointers to sub-objects within the message are reconstructed using the encoded present and not-present flags.

- All handles within the message are restored from the associated handle vector using the encoded present and not-present flags.

The resulting decoded message is ready to be consumed directly from memory.

Inlined Objects

Objects may also contain inlined objects which are aggregated within the body of the containing object, such as embedded structs and fixed-size arrays of structs.

Example

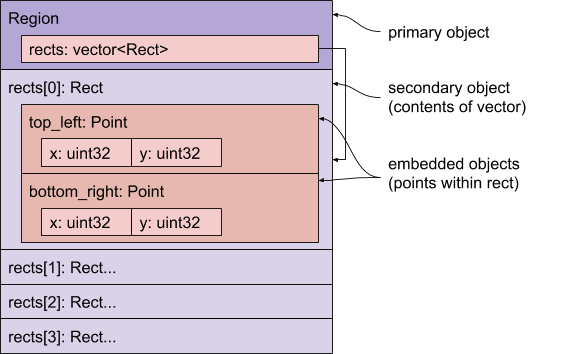

In the following example, the Region structure contains a vector of

Rect structures, with each Rect consisting of two Points.

Each Point consists of an x and y value.

type Region = struct {

rects vector<Rect>;

};

type Rect = struct {

top_left Point;

bottom_right Point;

};

type Point = struct {

x uint32;

y uint32;

};

Examining the objects in traversal order means that we start with the

Region structure — it's the primary object.

The rects member is a vector, so its contents are stored out-of-line.

This means that the vector content immediately follows the Region object.

Each Rect struct contains two Points, which are stored in-line

(because there are a fixed number of them), and each of the Points'

primitive data types (x and y) are also stored in-line.

The reason is the same; there is a fixed number of the member types.

We use in-line storage when the size of the subordinate object is fixed, and out-of-line when it's variable (including boxed structs).

Type Details

In this section, we illustrate the encodings for all FIDL objects.

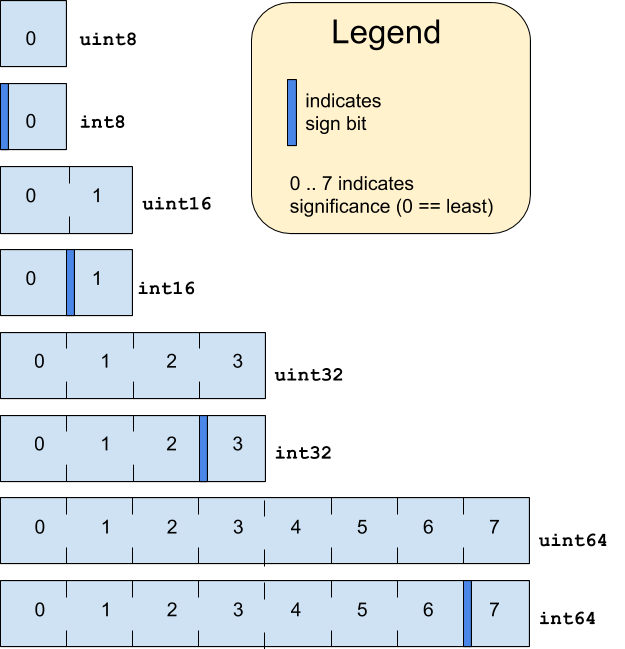

Primitives

- Value stored in little-endian format.

- Packed with natural alignment.

- Each m-byte primitive is stored on an m-byte boundary.

- Not optional.

The following primitive types are supported:

| Category | Types |

|---|---|

| Boolean | bool |

| Signed integer | int8, int16, int32, int64 |

| Unsigned integer | uint8, uint16, uint32, uint64 |

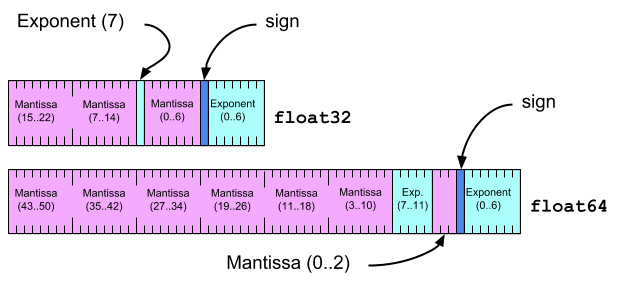

| IEEE 754 floating-point | float32, float64 |

| strings | (not a primitive, see Strings) |

Number types are suffixed with their size in bits.

The Boolean type, bool, is stored as a single byte, and has only the

value 0 or 1.

All floating point values represent valid IEEE 754 bit patterns.

Enums and Bits

Bit fields and enumerations are stored as their underlying primitive

type (e.g., uint32).

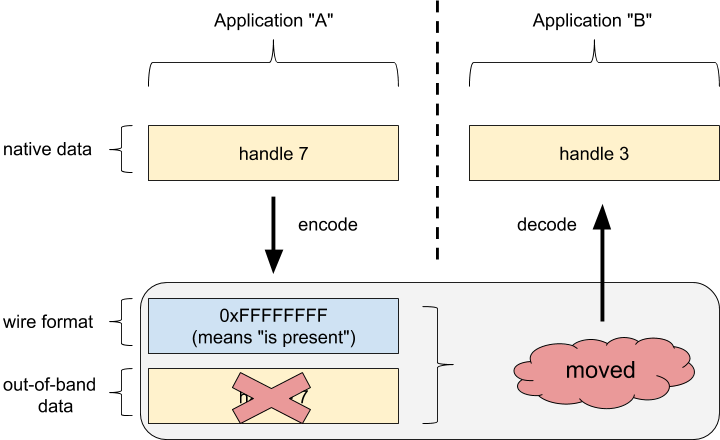

Handles

A handle is a 32-bit integer, but with special treatment. When encoded for transfer, the handle's on-wire representation is replaced with a present and not-present indication, and the handle itself is stored in a separate handle vector. When decoded, the handle presence indication is replaced with zero (if not present) or a valid handle (if present).

The handle value itself is not transferred from one application to another.

In this respect, handles are like pointers; they reference a context that's unique to each application. Handles are moved from one application's context to the other's.

The value zero can be used to indicate a optional handle is absent1.

See Life of a handle for a detailed example of transferring a handle over FIDL.

Aggregate objects

Aggregate objects serve as containers of other objects. They may store that data in-line or out-of-line, depending on their type.

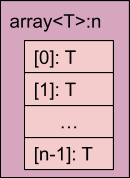

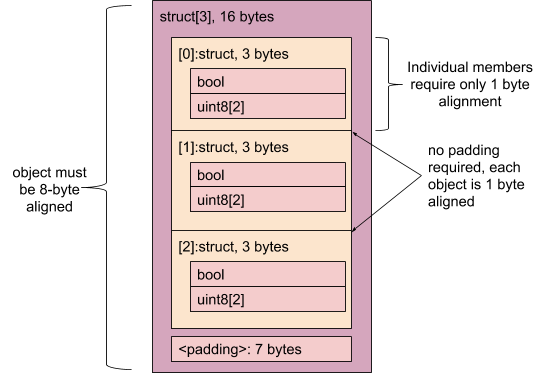

Arrays

- Fixed length sequence of homogeneous elements.

- Packed with natural alignment of their elements.

- Alignment of array is the same as the alignment of its elements.

- Each subsequent element is aligned on element's alignment boundary.

- The stride of the array is exactly equal to the size of the element (which includes the padding required to satisfy element alignment constraints).

- Never optional.

- There is no special case for arrays of bools. Each bool element takes one byte as usual.

Arrays are denoted:

array<T, N>: where T can be any FIDL type (including an array) and N is the number of elements in the array. Note: An array's size MUST be no more than 232-1. For additional details, see RFC-0059.

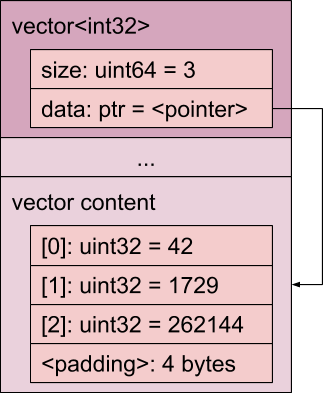

Vectors

- Variable-length sequence of homogeneous elements.

- Can be optional; absent vectors and empty vectors are distinct.

- Can specify a maximum size, e.g.

vector<T>:40for a maximum 40 element vector. - Stored as a 16 byte record consisting of:

size: 64-bit unsigned number of elements Note: A vector's size MUST be no more than 232-1. For additional details, see RFC-0059.data: 64-bit presence indication or pointer to out-of-line element data

- When encoded for transfer,

dataindicates presence of content:0: vector is absentUINTPTR_MAX: vector is present, data is the next out-of-line object

- When decoded for consumption,

datais a pointer to content:0: vector is absent<valid pointer>: vector is present, data is at indicated memory address

- There is no special case for vectors of bools. Each bool element takes one byte as usual.

Vectors are denoted as follows:

vector<T>: required vector of element type T (validation error occurs ifdatais absent)vector<T>:optional: optional vector of element type Tvector<T>:N,vector<T>:<N, optional>: vector with maximum length of N elements

T can be any FIDL type.

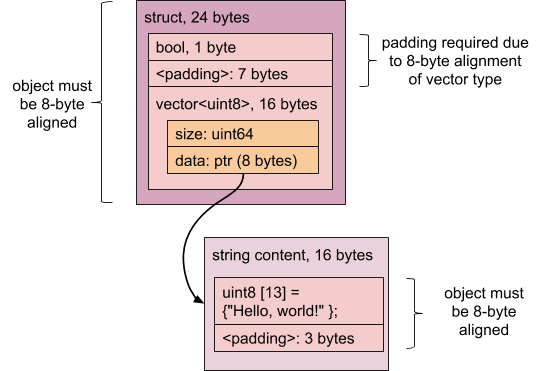

Strings

Strings are implemented as a vector of uint8 bytes, with the constraint

that the bytes MUST be valid UTF-8.

Structures

A structure contains a sequence of typed fields.

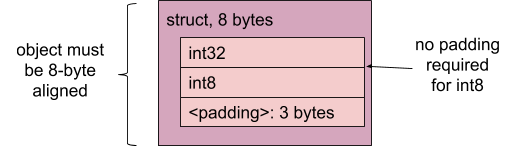

Internally, the structure is padded so that all members are aligned to the largest alignment requirement of all members. Externally, the structure is aligned on an 8-byte boundary, and may therefore contain final padding to meet that requirement.

Here are some examples.

A struct with an int32 and an int8 field has an alignment of 4 bytes (due to the int32), and a size of 8 bytes (3 bytes of padding after the int8):

A struct with a bool and a string field has an alignment of 8 bytes (due to the string) and a size of 24 bytes (7 bytes of padding after the bool):

A struct with a bool and two uint8 fields has an alignment of 1 byte and a size of 3 bytes (no padding!):

A structure can be:

- empty — it has no fields. Such a structure is 1 byte in size, with an

alignment of 1 byte, and is exactly equivalent to a structure containing a

uint8with the value zero. - required — the structure's contents are stored in-line.

- optional — the structure's contents are stored out-of-line and accessed through an indirect reference.

Storage of a structure depends on whether it is boxed at the point of reference.

- Non-boxed structures:

- Contents are stored in-line within their containing type, enabling very efficient aggregate structures to be constructed.

- The structure layout does not change when inlined; its fields are not repacked to fill gaps in its container.

- Boxed structures:

- Contents are stored out-of-line and accessed through an indirect reference.

- When encoded for transfer, stored reference indicates presence of structure:

0: reference is absentUINTPTR_MAX: reference is present, structure content is the next out-of-line object- When decoded for consumption, stored reference is a pointer:

0: reference is absent<valid pointer>: reference is present, structure content is at indicated memory address

Structs are denoted by their declared name (e.g. Circle) and can be boxed:

Point: requiredPointbox<Color>: boxed, always optionalColor

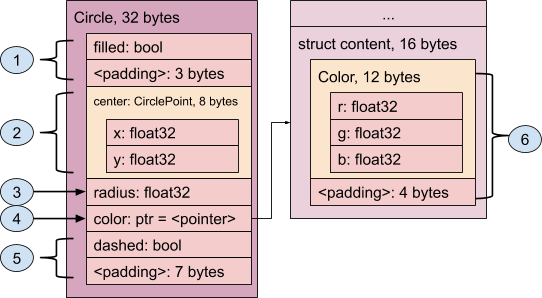

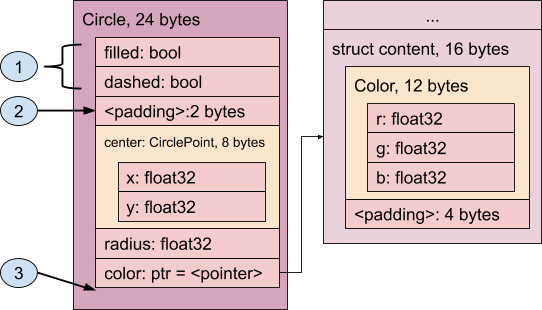

The following example illustrates:

- Structure layout (order, packing, and alignment)

- A required structure (

Point) - A boxed (

Color)

type Circle = struct {

filled bool;

center CirclePoint; // CirclePoint will be stored in-line

radius float32;

color box<Color>; // Color will be stored out-of-line

dashed bool;

};

type CirclePoint = struct {

x float32;

y float32;

};

type Color = struct {

r float32;

g float32;

b float32;

};

The Color content is padded to the 8 byte secondary object alignment boundary.

Going through the layout in detail:

- The first member,

filled bool, occupies one byte, but requires three bytes of padding because of the next member, which has a 4-byte alignment requirement. - The

center CirclePointmember is an example of a required struct. As such, its content (thexandy32-bit floats) are inlined, and the entire thing consumes 8 bytes. radiusis a 32-bit item, requiring 4 byte alignment. Since the next available location is already on a 4 byte alignment boundary, no padding is required.- The

color box<Color>member is an example of a boxed structure. Since thecolordata may or may not be present, the most efficient way of handling this is to keep a pointer to the structure as the in-line data. That way, if thecolormember is indeed present, the pointer points to its data (or, in the case of the encoded format, indicates "is present"), and the data itself is stored out-of-line (after the data for theCirclestructure). If thecolormember is not present, the pointer isNULL(or, in the encoded format, indicates "is not present" by storing a zero). - The

dashed booldoesn't require any special alignment, so it goes next. Now, however, we've reached the end of the object, and all objects must be 8-byte aligned. That means we need an additional 7 bytes of padding. - The out-of-line data for

colorfollows theCircledata structure, and contains three 32-bitfloatvalues (r,g, andb); they require 4 byte alignment and so can follow each other without padding. But, just as in the case of theCircleobject, we require the object itself to be 8-byte aligned, so 4 bytes of padding are required.

Overall, this structure takes 48 bytes.

By moving the dashed bool to be immediately after the filled bool, though,

you can realize significant space savings 2:

- The two

boolvalues are "packed" together within what would have been wasted space. - The padding is reduced to two bytes — this would be a good place to

add a 16-bit value, or some more

bools or 8-bit integers. - Notice how there's no padding required after the

Colorbox; everything is perfectly aligned on an 8 byte boundary.

The structure now takes 40 bytes.

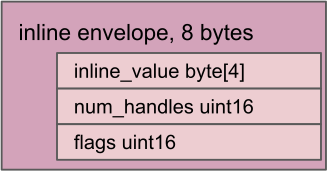

Envelopes

An envelope is a container for data, used internally by tables and unions. It is not exposed to the FIDL language. It has a fixed, 8 byte format.

An envelope header that is all zeros is referred to as the "zero envelope". It is used to represent an absent envelope. Otherwise, the envelope is present and bit 0 of its flags indicate whether the data is stored inline or out-of-line:

- If bit 0 is set, an inline representation is used.

- If bit 0 is unset an out-of-line representation is used.

Bit 0 may only be set if the size of the payload is <= 4 bytes. Bit 0 may be unset only if either the envelope is the zero envelope or the size of the payload is > 4 bytes.

Having num_bytes and num_handles allows us to skip unknown envelope content.

num_bytes will always be a multiple of 8 because out-of-line objects are

8 byte aligned.

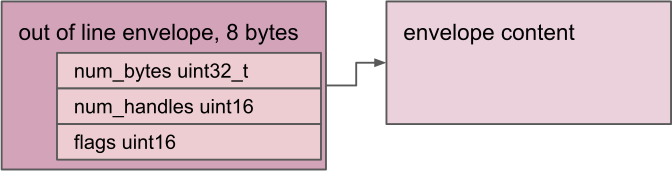

Tables

- Record type consisting of the number of elements and a pointer.

- Pointer points to an array of envelopes, each of which contains one element.

- Each element is associated with an ordinal.

- Ordinals are sequential, gaps incur an empty envelope cost and hence are discouraged.

Tables are denoted by their declared name (e.g., Value), and are never optional:

Value: requiredValue

The following example shows how tables are laid out according to their fields.

type Value = table {

1: command int16;

2: data Circle;

3: offset float64;

};

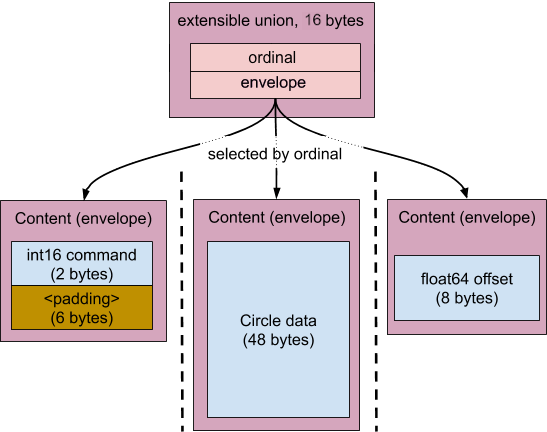

Unions

- Record type consisting of an ordinal and an envelope.

- Ordinal indicates member selection, and is represented with a uint64.

- Each element is associated with a user specified ordinal.

- Ordinals are sequential. Unlike tables, gaps in ordinals do not incur a wire format space cost.

- Absent optional unions are represented with a

0ordinal, and a zero envelope. - Empty unions are not allowed.

unions are denoted by their declared name (e.g. Value) and optionality:

Value: requiredValueValue:optional: optionalValue

The following example shows how unions are laid out according to their fields.

type UnionValue = strict union {

1: command int16;

2: data Circle;

3: offset float64;

};

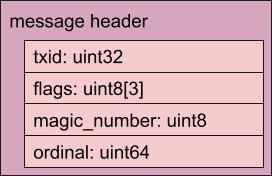

Transactional Messages

In a transactional message, there is always a header, followed by an optional body.

Both the header and body are FIDL messages, as defined above; that is, a collection of data.

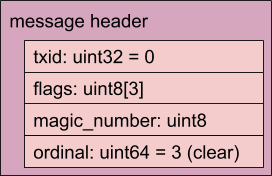

The header has the following form:

zx_txid_t txid, transaction ID (32 bits)txids with the high bit set are reserved for use by zx_channel_call()txids with the high bit unset are reserved for use by userspace- A value of

0fortxidis reserved for messages that do not require a response from the other side. Note: For more details ontxidallocation, see zx_channel_call().

uint8[3] flags, MUST NOT be checked by bindings. These flags can be used to enable soft transitions of the wire format. See Header Flags for a description of the current flag definitions.uint8 magic number, determines if two wire formats are compatible.uint64 ordinal- The zero ordinal is invalid.

- Ordinals with the most significant bit set are reserved for control messages and future expansion.

- Ordinals without the most significant bit set indicate method calls and responses.

There are three kinds of transactional messages:

- method requests,

- method responses, and

- event requests.

We'll use the following interface for the next few examples:

type DivisionError = strict enum : uint32 {

DIVIDE_BY_ZERO = 1;

};

protocol Calculator {

Add(struct {

a int32;

b int32;

}) -> (struct {

sum int32;

});

Divide(struct {

dividend int32;

divisor int32;

}) -> (struct {

quotient int32;

remainder int32;

}) error DivisionError;

Clear();

-> OnError(struct {

status_code uint32;

});

};

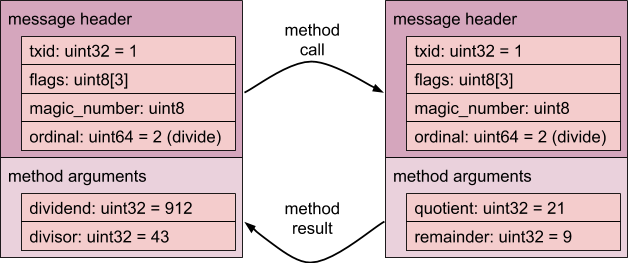

The Add() and Divide() methods illustrate both the method request (sent from the client to the server), and a method response (sent from the server back to the client).

The Clear() method is an example of a method request that does not have a body.

It's not correct to say it has an "empty" body: that would imply that there's a body following the header. In the case of Clear(), there is no body, there is only a header.

Method Request Messages

The client of an interface sends method request messages to the server in order to invoke the method.

Method Response Messages

The server sends method response messages to the client to indicate completion of a method invocation and to provide a (possibly empty) result.

Only two-way method requests that are defined to provide a (possibly empty) result in the protocol declaration will elicit a method response. One-way method requests must not produce a method response.

A method response message provides the result associated with a prior method request. The body of the message contains the method results as if they were packed in a struct.

Here we see that the answer to 912 / 43 is 21 with a remainder of 9.

Note the txid value of 1 — this identifies the transaction.

The ordinal value of 2 indicates the method — in this case, the

Divide() method.

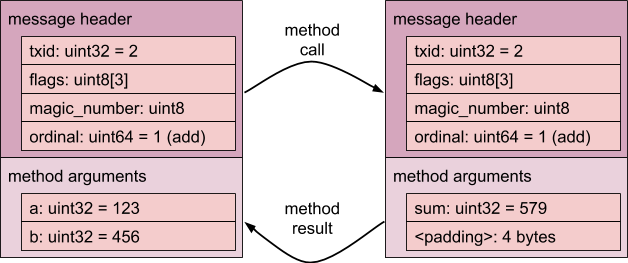

Below, we see that 123 + 456 is 579.

Here, the txid value is now 2 — this is simply the next transaction

number assigned to the transaction.

The ordinal is 1, indicating Add(), and note that the result requires

4 bytes of padding in order to make the body object have a size that's

a multiple of 8 bytes.

And finally, the Clear() method is different than the Add() and

Divide() in two important ways:

* it does not have a body (that is, it consists solely of the header), and

* it does not solicit a response from the interface (txid is zero).

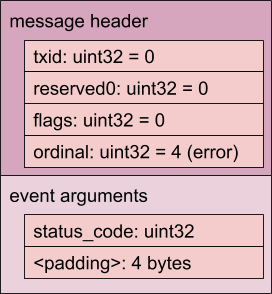

Event Requests

An example of an event is the OnError() event in our Calculator.

The server sends an unsolicited event request to the client to indicate that an asynchronous event occurred, as specified by the protocol declaration.

In the Calculator example, we can imagine that an attempt to divide by zero

would cause the OnError() event to be sent with a "divide by zero" status code

prior to the connection being closed. This allows the client to distinguish

between the connection being closed due to an error, as opposed to for other

reasons (such as the calculator process terminating abnormally).

Notice how the txid is zero (indicating this is not part of a transaction),

and ordinal is 4 (indicating the OnError() method).

The body contains the event arguments as if they were packed in a struct, just as with method result messages. Note that the body is padded to maintain 8-byte alignment.

Epitaph (Control Message Ordinal 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF)

An epitaph is an event (txid zero) with ordinal 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF. A server may send an epitaph as the last message prior to closing the connection, to provide an indication of why the connection is being closed. No further messages may be sent through the connection after the epitaph. Epitaphs are not sent from clients to servers.

An epitaph's wire representation is equivalent to this FIDL:

fidl

struct {

error zx.Status;

};

Epitaphs may be formally defined in FIDL in the future.

Details

Size and Alignment

sizeof(T) denotes the size in bytes for an object of type T.

alignof(T) denotes the alignment factor in bytes to store an object of type T.

FIDL primitive types are stored at offsets in the message that are a multiple

of their size in bytes. Thus for primitives T, alignof(T) ==

sizeof(T). This is called natural alignment. It has the

nice property of satisfying typical alignment requirements of modern CPU

architectures.

FIDL complex types, such as structs and arrays, are stored at offsets in the

message that are a multiple of the maximum alignment factor of all of their

fields. Thus for complex types T, alignof(T) ==

max(alignof(F:T)) over all fields F in T. It has the nice

property of satisfying typical C structure packing requirements (which can be

enforced using packing attributes in the generated code). The size of a complex

type is the total number of bytes needed to store its members properly aligned

plus padding up to the type's alignment factor.

FIDL primary and secondary objects are aligned at 8-byte offsets within the message, regardless of their contents. The primary object of a FIDL message starts at offset 0. Secondary objects, which are the only possible referent of pointers within the message, always start at offsets that are a multiple of 8. (So all pointers within the message point at offsets that are a multiple of 8.)

FIDL in-line objects (complex types embedded within primary or secondary objects) are aligned according to their type. They are not forced to 8 byte alignment.

Types

Notes:

- N indicates the number of elements, whether stated explicitly (as in

array<T, N>, an array with N elements of type T) or implicitly (atableconsisting of 7 elements would haveN=7). - The out-of-line size is always padded to 8 bytes. We indicate the content size below, excluding the padding.

sizeof(T)in thevectorentry below is

in_line_sizeof(T) + out_of_line_sizeof(T).- M in the

tableentry below is the maximum ordinal of present field. - In the

structentry below, the padding refers to the required padding to make thestructaligned to the widest element. For example,struct{uint32;uint8}has 3 bytes of padding, which is different than the padding to align to 8 bytes boundaries.

| Type(s) | Size (in-line) | Size (out-of-line) | Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|

bool |

1 | 0 | 1 |

int8, uint8 |

1 | 0 | 1 |

int16, uint16 |

2 | 0 | 2 |

int32, uint32, float32 |

4 | 0 | 4 |

int64, uint64, float64 |

8 | 0 | 8 |

enum, bits |

(underlying type) | 0 | (underlying type) |

handle, et al. |

4 | 0 | 4 |

array<T, N> |

sizeof(T) * N | 0 | alignof(T) |

vector, et al. |

16 | N * sizeof(T) | 8 |

struct |

sum(sizeof(fields)) + padding | 0 | 8 |

box<struct> |

8 | sum(sizeof(fields)) + padding | 8 |

envelope |

8 | sizeof(field) | 8 |

table |

16 | M * sizeof(envelope) + sum(aligned_to_8(sizeof(present fields)) | 8 |

union, union:optional |

16 | sizeof(selected variant) | 8 |

The handle entry above refers to all flavors of handles, specifically

handle, handle:optional, handle:H, handle:<H, optional>,

client_end:Protocol, client_end:<Protocol, optional>,

server_end:Protocol, and server_end:<Protocol, optional>.

Similarly, the vector entry above refers to all flavors of vectors,

specifically vector<T>, vector<T>:optional, vector<T>:N,

vector<T>:<N, optional>, string, string:optional, string:N, and

string:<N, optional>.

Padding

The creator of a message must fill all alignment padding gaps with zeros.

The consumer of a message must verify that padding contains zeros (and generate an error if not).

Maximum Recursion Depth

FIDL vectors, optional structures, tables, and unions enable the construction of recursive messages. Left unchecked, processing excessively deep messages could lead to resource exhaustion, or undetected infinite looping.

For safety, the maximum recursion depth for all FIDL messages is limited to 32 levels of indirection. A FIDL encoder, decoder, or validator MUST enforce this limit by keeping track of the current recursion depth during message validation.

Formal definition of recursion depth:

- The inline object of a FIDL message is defined to be at recursion depth 0.

- Each traversal of an indirection, through a pointer or an envelope, increments the recursion depth by 1.

If at any time the recursion depth exceeds 32, the operation must be terminated and an error raised.

Consider for instance:

type InlineObject = struct {

content_a string;

vector vector<OutOfLineStructAtLevel1>;

table TableInlineAtLevel0;

};

type OutOfLineStructAtLevel1 = struct {

content_b string;

};

type TableInlineAtLevel0 = table {

1: content_c string;

};

When encoding an instance of an InlineObject, we have the respective recursion depths:

- The bytes of

content_aare at a recursion depth of 1, i.e. thecontent_astring header is inline within theInlineObjectstruct, and the bytes are in an out-of-line object accessible through a pointer indirection. - The bytes of

content_bare at a recursion depth of 2, i.e. thevectorheader is inline within theInlineObjectstruct, theOutOfLineStructAtLevel1structs are therefore at recursive depth 1, thecontent_bstring header is inline withinOutOfLineStructAtLevel1, and the bytes are in an out-of-line object accessible through a pointer indirection from depth 1, making them at depth 2. - The bytes of

content_care at a recursion depth of 3, i.e. thetableheader is inline within theInlineObjectstruct, the table envelope is at a depth of 1, pointing to thecontent_cstring header at a depth of 2, and the bytes are in an out-of-line object accessible through a pointer indirection, making them at depth 3.

Validation

The purpose of message validation is to discover wire format errors early before they have a chance to induce security or stability problems.

Message validation is required when decoding messages received from a peer to prevent bad data from propagating beyond the service entry point.

Message validation is optional but recommended when encoding messages to send to a peer in order to help localize violated integrity constraints.

To minimize runtime overhead, validation should generally be performed as part of a single pass message encoding or decoding process, such that only a single traversal is needed. Since messages are encoded in depth-first traversal order, traversal exhibits good memory locality and should therefore be quite efficient.

For simple messages, validation may be very trivial, amounting to no more than a few size checks. While programmers are encouraged to rely on their FIDL bindings library to validate messages on their behalf, validation can also be done manually if needed.

Conformant FIDL bindings must check all of the following integrity constraints:

- The total size of the message including all of its out-of-line sub-objects exactly equals the total size of the buffer that contains it. All sub-objects are accounted for.

- The total number of handles referenced by the message exactly equals the total size of the handle table. All handles are accounted for.

- The maximum recursion depth for complex objects is not exceeded.

- All enum values fall within their defined range.

- All union tag values fall within their defined range.

- Encoding only:

- All pointers to sub-objects encountered during traversal refer precisely to the next buffer position where a sub-object is expected to appear. As a corollary, pointers never refer to locations outside of the buffer.

- Decoding only:

- All present and not-present flags for referenced sub-objects hold the value 0 or UINTPTR_MAX only.

- All present and not-present flags for referenced handles hold the value 0 or UINT32_MAX only.

Header Flags

Flags[0]

| Bit | Current Usage | Past Usages |

|---|---|---|

| 7 (MSB) | Unused | |

| 6 | Unused | |

| 5 | Unused | |

| 4 | Unused | |

| 3 | Unused | |

| 2 | Unused | |

| 1 | Indicates whether the v2 wire format is used (RFC-0114) | |

| 0 | Unused | Indicates whether static unions should be encoded as xunions (RFC-0061) |

Flags[1]

| Bit | Current Usage | Past Usages |

|---|---|---|

| 7 (MSB) | Unused | |

| 6 | Unused | |

| 5 | Unused | |

| 4 | Unused | |

| 3 | Unused | |

| 2 | Unused | |

| 1 | Unused | |

| 0 | Unused |

Flags[2]

| Bit | Current Usage | Past Usages |

|---|---|---|

| 7 (MSB) | Unused | |

| 6 | Unused | |

| 5 | Unused | |

| 4 | Unused | |

| 3 | Unused | |

| 2 | Unused | |

| 1 | Unused | |

| 0 | Unused |

-

Defining the zero handle to mean "there is no handle" means it is safe to default-initialize wire format structures to all zeros. Zero is also the value of the

ZX_HANDLE_INVALIDconstant. ↩ -

Read The Lost Art of Structure Packing for an in-depth treatise on the subject. ↩