Since it is impractical to request of a programmer to know by heart a magic

key referring to a specific message, it stands to reason that the localization

system should provide an ergonomic way to refer to these keys in a symbolic

manner (remember the abstract example for MSG_Hello_World above.

Following the best practices for 18n and l10n, the source strings live in an

XML file (here, named strings.xml), explained below. An

example of a strings.xml file is shown below.

The goal of this file is to declare all externalized strings that our program

uses, and give them a locally unique name. The strings will be used as a

basis for translation, and names will be used as a basis for the symbolic

xml

<!-- comment -->

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<resources xmlns:xliff="urn:oasis:names:tc:xliff:document:1.2">

<!-- comment -->

<string

name="STRING_NAME"

>text_string</string>

<string

name="STRING_NAME_2"

>text_string_2</string>

<string

name="STRING_NAME_3"

>string with

an intervening newline</string>

</resources>

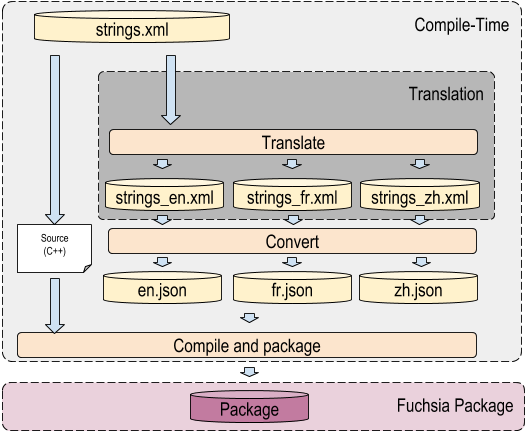

The file strings.xml goes through a series of transformations in which

language-specific varieties of the same file are produced by translators. The

input-output behavior of the translation process is: strings.xml file goes

in, with strings written in some source (human) language, and multiple flavors

of strings.xml come out, each translated in a particular single language.

The entire translation process can be quite involved, in a large organization

it can involve farming tasks out to translators who may live around the world,

and scores of dedicated translation tooling. but the precise mechanics of the

box does not matter too much to us as consumers as long as the input-output

behavior of the process is upheld, and we're generally aware that the

translation could take a while. The resulting files are converted into a

machine-readable form, and shipped alongside a Fuchsia program within the same

Fuchsia package

.

An important feature of Fuchsia packages is that they are inherently not an

archive, but rather a manifest that points to files by their content hash. So

multiple programs can share the same files, and languages closely related

("en-US", "en-GB") can potentially share message disk space. The following

diagram shows a compact overview of the lifecycle of strings.

strings.xml

We are reusing the Android string resources XML format to represent localizable strings. Since we will be adding nothing to the strings.xml format, the full discussion of the features is delegated to the string resources page.

While all that XML in the above diagram makes this discussion look like it just emerged from some wormhole connected straight to the 1990s, XML is actually a very good fit to describe annotated text. strings.xml is a format that has been time-tested in Android so we know it will be adequate, and developers are familiar with it.

For example, a string resource can be declared with annotations interleaved into the source text.

<!-- … -->

<string name="title"

>Best practices for <annotation font="title_emphasis">text</annotation> look like so</string>

<!-- … -->

Above: An example interleaving of translation text and annotation._

It is possible to interleave text that should be protected from translation, like so:

<string name="countdown">

<xliff:g id="time" example="5 days"

>{1}</xliff:g> until holiday</string>

Above:: An example of an interleaving of a fenced-off parameter, annotated with an example value and guarded with a tag that is not part of the string resources data schema._

We can also define our own additions to the data schema if we so need, and interleave that data schema transparently in an existing schema.

There are some necessary constraints on the contents of the file above:

- Every

nameattribute in the file must be unique. - Name identifiers may contain uppercase and lowercase ASCII letters, digits and underscores, but may not start with a number. So for example,

_H_e_L_L_o_wo_1_rldis allowed, but0coolis not. - No two

name-messagecombinations in the file may repeat.

For the time being there are no provisions for having multiple strings files in a project.

Message identifiers

The message identifiers (the "magical" numeric constants for each message) are

generated based on the contents of the strings.xml file. Every string

message gets a unique identifier, which is computed based on the one-way hash

on name and the contents of the message itself. This identifier assignment

ensures that it is vanishingly unlikely for two different messages to

accidentally have the same resulting identifier.

The generation of these messages is automated by GN build rules in Fuchsia, but is ultimately performed by a program called strings_to_fidl. This program generates FIDL intermediate representation for the message IDs, and the regular FIDL toolchain is used to produce language-specific versions of that info. As an example, the C++ flavor would be a header file with the following content:

namespace fuchsia {

namespace intl {

namespace l10n {

enum class MessageIds : uint64_t {

STRING_NAME = 42u,

STRING_NAME_2 = 43u,

STRING_NAME_3 = 44u,

};

} // namespace l10n

} // namespace intl

} // namespace fuchsia

The precise values assigned to each particular enum value in the example above are not relevant. The generation method is also not relevant at this time, since all identifiers are generated at compile time and there is no opportunity for version skew. We may for now safely assume that an identical name-content combination will always have the same message ID assigned.

It is fairly easy to include the resulting file into a C++ program. A minimal

example is given below, but refer to the fully worked-out example for the

precise details of the wire-up. The library parameter fuchsia.intl.l10n is

provided directly by the author as a flag to strings_to_fidl; or if the

appropriate GN template is used, as a parameter to the GN template.

#include <iostream>

// This header file has been generated from the strings library fuchsia.intl.l10n.

#include "fuchsia/intl/l10n/cpp/fidl.h"

// Each library name segment between dots gets its own nested namespace in

// the generated C++ code.

using fuchsia::intl::l10n::MessageIds;

int main() {

std::cout << "Constant: " << static_cast<uint64_t>(MessageIds::STRING_NAME) << std::endl;

return 0;

}

*.json

The FIDL and C++ code generation makes the message IDs available to the program authors. On the packaging side, we also must provide the localized asset for each language we support. At present the encoding for this information is JSON. This was done for expedience, but a number of improvements can be made on that decision to improve performance and security.

Generating this information is delegated to the program named

strings_to_json,

which merges the original strings.xml with a language specific

file (for example, a French translation lives in strings_fr.xml).

Again, for builds driven by GN, the invocation of strings_to_json

is encapsulated in a build rule.

Example contents of a generated JSON file are given below.

{

"locale_id": "fr",

"source_locale_id": "en-US",

"num_messages": 3,

"messages": {

"42": "le string",

"43": "le string 2",

"44": "le string\nwith intervening newline"

}

}

The JSON format has the following fields currently defined. In case the table below goes out of date, the source of truth for the JSON structure is the strings model.

| Field | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

locale_id |

Locale ID (string) | The locale for which the messages are translated. |

source_locale_id |

Locale ID (string) | The locale of the source message file. |

num_messages |

Positive integer | The number of messages that were present in the original strings.xml. This allows us to estimate quickly the quality of the translation by comparing that number of messages with the number of messages that are present in the JSON file. |

messages |

Map [u64->string] |

A map from message ID to the appropriate message. |